Questioning the Orders

Questioning the Orders

Shalom,

This Shabbat we will be reading Torah portion “Ki Tavo” in the book of Deuteronomy – Devarim.

This Torah portion includes the laws of the tithes given to the Levites and to the poor, and detailed instructions on how to proclaim the blessings and the curses on Mount Gerizim and Mount Eival.

After listing the blessings with which G‑d will reward the people when they follow the laws of the Torah, Moses gives a long account of the bad things illness, famine, poverty and exile—that shall befall them if they abandon G‑d’s commandments.

Moses concludes by telling the people that only today, forty years after their birth as a people, have they attained “a heart to know, eyes to see and ears to hear.”

Obeying the Orders

It is interesting to point out that there are 613 commandments – מצוות (mitzvot) in the Torah, but there is no word in biblical Hebrew that means “to obey”.

When Hebrew was revived as modern language the word, le’tzayet – לציית (to obey) was borrowed from Aramaic.

Until then, actually there was no Hebrew word for “to obey.”

What then does the Torah use as the appropriate response to a commandment – mitzvah?

It is:

Shema – שמע

The verb sh-m-a שמע is a keyword in the book of Deuteronomy, where it occurs 92 times, usually in the sense of what God wants from us in response to the commandments.

But the verb sh-m-a means many things. Here are some of the meanings it has in Genesis:

“To hear”, “To listen, pay attention, heed” “To understand”.

The most famous verse that includes this verb is of course:

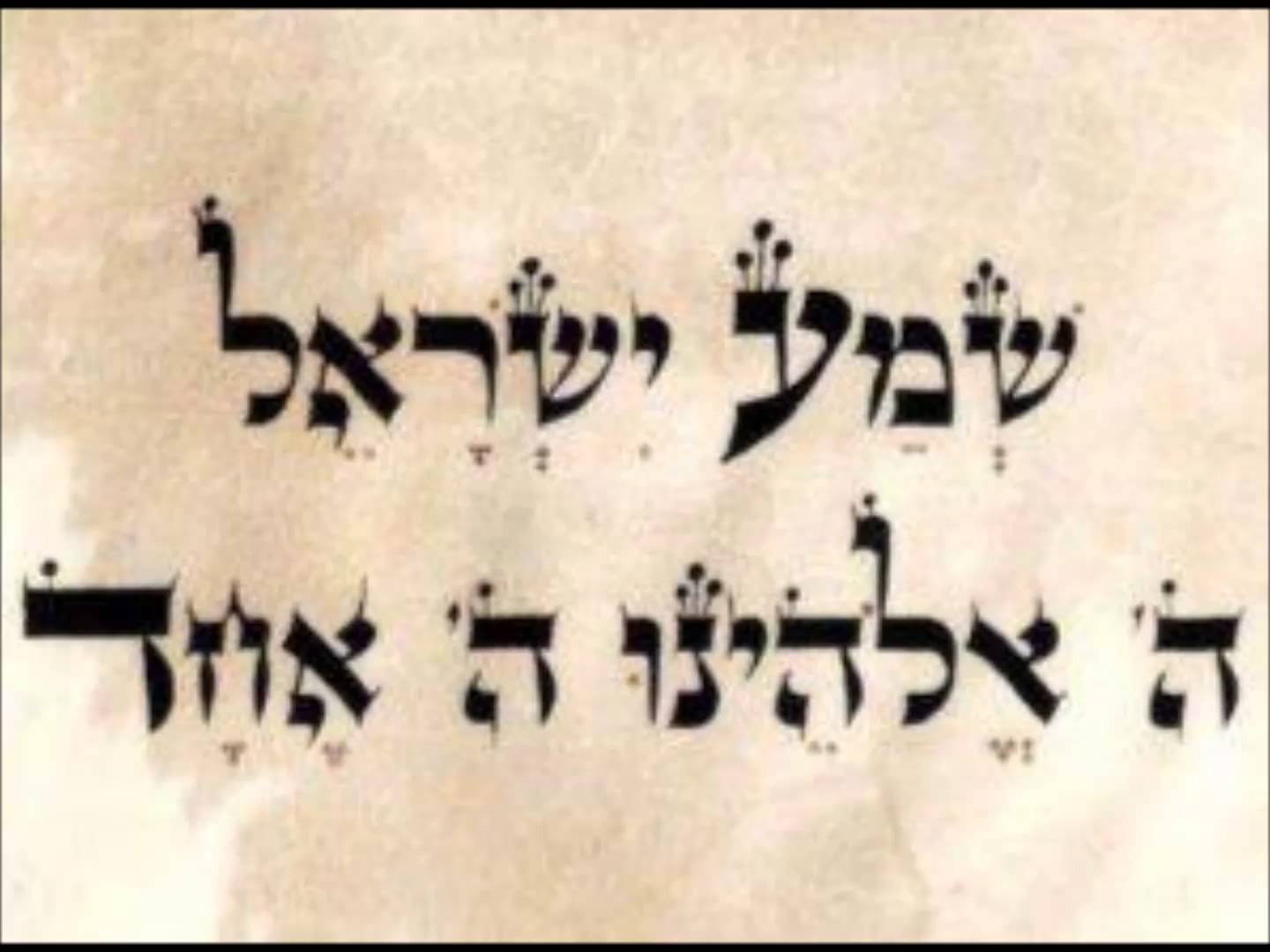

שְׁמַע יִשְׂרָאֵל, ה’ אֱלהֵינוּ, ה’ אֶחָד

Hear, O Israel: the Lord our God, the Lord is one

(Deut, 6:4)

The fact that sh-m-a means all these different things suggests that in the Torah there is no concept of blind obedience.

Throughout the book of Devarim (Deuteronomy) Moses explains to the new generation who will eventually conquer and inhabit the land, that the laws God has given them are not just Divine decrees.

They make sense in human terms. They respect human dignity. They honor the integrity of nature. They give the land the chance to rest and recuperate. They protect Israel against the otherwise inexorable laws of the decline and fall of nations.

In general, a commander orders and a soldier obeys.

But that is not how the Torah conceives the relationship between God and his people. God, who created us in His image, giving us freedom and the power to think, wants us to understand His commands.

The Torah is unique among all the other doctrines and religions that other nations have had, in that our Torah contains nothing that does not originate in equity and reason.

That is why Moses, consistently throughout the book of Devarim, uses the verb sh-m-a – שמע.

He wants the people of Israel to obey God, but not blindly or through fear alone. The Israelites should know this through their own direct experience.

God had not given the Torah to Israel for His sake but for theirs.

That is the meaning of Moses’ great words in this week’s Torah portion:

הַסְכֵּת וּשְׁמַע, יִשְׂרָאֵל

הַיּוֹם הַזֶּה נִהְיֵיתָ לְעָם, לה’ אֱלֹהֶיךָ

Be silent, Israel, and listen

You have today become the people of the Lord your God.

(Deut. 27: 9)

(The people of Israel are unique among the peoples of the world:

Their nationhood was forged not at the point at which they gained their own land, or developed a common language or culture, but on the day on which they pledged to uphold the Torah…) R. Shimshon Raphael Hirsch.

Keeping the commands involves an act of listening, not just submission and blind obedience.

It means trying to understand our limits and imperfections as human beings. It means remembering what it felt like to be a slave in Egypt. It involves humility and memory and gratitude.

God is not a tyrant but a teacher. He seeks not just our obedience but also our understanding.

All nations have laws, and laws are there to be obeyed.

People of Israel, however, set it as their highest task to understand why the law is as it is.

That is what the Torah means by the word:

SH-M-A – שמע

(Based on Rabbi J. Sacks’ article).

Shabbat Shalom,